Films

MOVING PICTURES

Films made from photographic images

FRAGMENTS

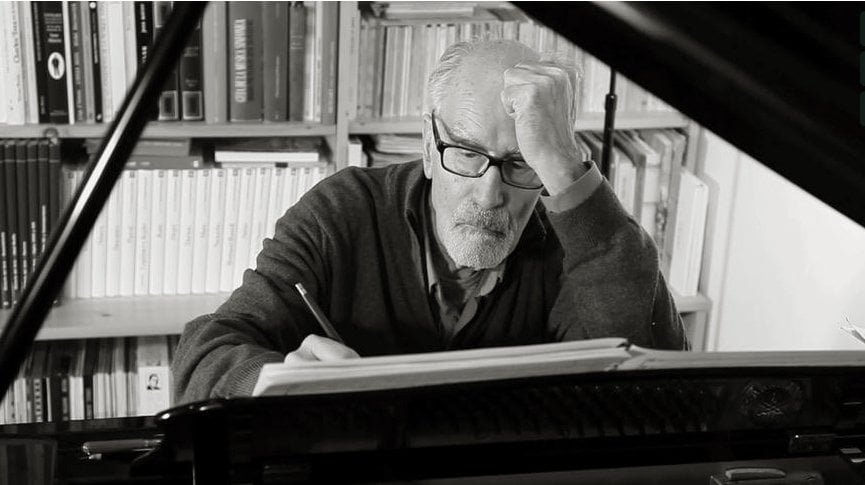

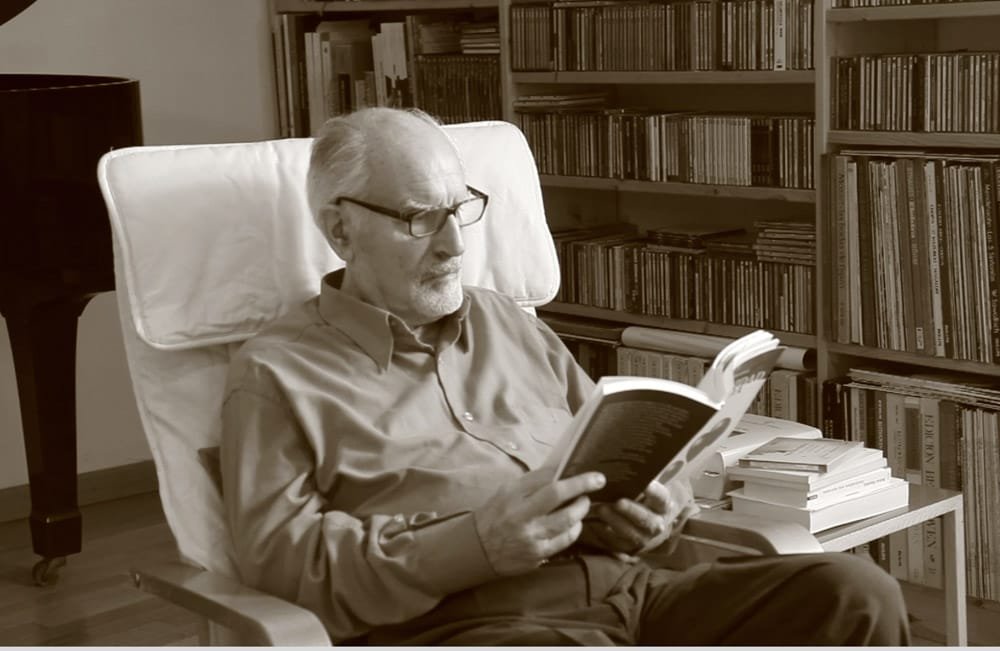

Inspired by seven of my photographs, Eduardo Rincón composed a 48-minute piece for piano in 14 movements structured along the lines of Modest Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition.”

Fragments is my own interpretation of the composer Rincón’s state of mind, my own sense of why he chose the photographs he did and how they relate to his own life experience (he spent years in Franco’s prisons for ‘political’ reasons, the first time at age 15 because they couldn’t find his brother). It is, in essence, a tale about a tale about a tale.

IMAGES FOR AN EXHIBITION

Images for an Exhibition at the Church of St Mary of Albarracín, 2012.

The full concert can be listened to here:

SEVEN LOOKS

There is no doubt that photography has reached the level of expression and aesthetics that today stands as another of the forms of artistic expression in the arts. It is not easy to achieve this condition when you are subject to a machine, and the means to reach art, through this mechanical exposition, is not easy to attain. It’s not the hand that conveys the perception of time, the contact with the subject, and less if it is a human figure – the environment, the light, the moment of firing, finding that second makes possible the perception of that moment – a whole number of conditions that require perceptual qualities that are not common, and in a way, or you have it or it is very difficult to acquire. As in all art, you either reach or you don’t the height that is necessary to make a work, in this case a photograph, into a true work of art.

In the case of Michael Dunev we find that which is most unusual: a photographer artist. He has that essential sense of space and time, that dramatic intution that announces (or denounces, and in this case it acquires an incalculable artistic value), something which permits him to perceive where the movement is, retaining at the same time the potential drama of the situation portrayed, not only with individuals, but also in things, the story they tell, the beauty they contain, what they carry or what can become of them. I believe that there is no great photograph if we can not transcribe in it a story that moves us, one that weaves an event, allows us to feel the pain or joy of a situation that has occurred or may yet occur. Photography requires a condition of human perception which is what makes it another (and not the least important) of the visual arts. Without this condition, we will see only “pictures,” poor memories of a boring holiday that maybe we’ll keep forgotten.

When Dunev showed me a collection of his photographs, I almost immediately asked permission to perform a musical vision on them. The work would be titled “Images for an Exhibition” and I naturally thought it would be a fitting tribute to Mussorgsky, since as in his extraordinary “Pictures”, each photograph will be accompanied by a Gaze, which would correspond to what he titled the Promenade. Both in the choice of titles as in the arrangement of the works, I must acknowledge the help of my partner Dolça, to whose common sense and keen sense of theater and literature I owe so much. Always an invaluable assistance, we chose the works that impressed me most at the time and I started working, numbering every Gaze and titling each piece, working with the idea that each Gaze would be a variation of the first, thus helping unite the whole.

I can only thank Miguel Dunev his generosity for allowing me to “sneak” into his work, and Santiago Barro, for his very important, generous and successful way in interpreting and understanding the work.

Eduardo Rincón

Torroella de Montgrí, 31 March, 2012

EDUARDO RINCÓN 1924 – 2023

MY LIFE

I was born in Santander on October 25, 1924, in one of the first numbers of Paseo de la Concepción. I think it was a second floor apartment that looked out onto the orchards between Calle de Tetuán and the promenade, which was the residence of the wealthy families (with the large houses on the seafront, better known then as the Muelle or those that continued along it towards San Martin and Paseo de Reina Victoria); naturally my house belonged to a small group of apartment houses, not a chalet, and my stay there was brief. I don’t know exactly when we moved to this modern house, with more light and sun, behind San Celedonio Street, but our time in this house also lasted very little before we moved to the apartment at Casimiro Sainz 17, 2nd floor, in the fishermen’s district of Puerto Chico, where I lived (with the obligatory breaks of trips and prisons), until I married Carmen, on December 26, 1947, and went to live in her parents’ house, on Fernández de Isla Street.

It was my school, one of the many that the Republic had built in the short time that the regime had before General Franco’s uprising, and I have wonderful memories of it and its teachers, which caused me numerous problems since it was difficult for me to return home once the study days were over: there was a library, painting and sculpture workshops, cinema once a week, chemistry laboratory (only for the last two courses, of course)… it was and continues to be in my memory, something exceptional. Don Jesús Revaque and his team of magnificent teachers, all but three of them were forced into exile when the rebel troops entered the city during the Civil War from 1936 to 1939.

I too left, a few months later, at the end of the summer of 1936, for my first exile. My parents (a serious but understandable mistake) decided that for greater security against the bombings of the German and Italian air force, which were supporting the coup d’état of the Spanish right, we should leave for France, taking advantage of the flight of my aunt Araceli, who in turn was following the exile that my uncle Ángel, who had a certain political relevance, was forced into. Thus, around the month of July or beginning of August of that year, we left on a freight train for Asturias, where a few hundred refugees were awaited by the freighter called the “Seven Seas Spray”, which through the Cantabrian Sea, with a slight swell and pursued by the battleship “Almirante Cervera”, a warship at the service of the rebels, managed to reach French jurisdictional waters and deposit us in Bordeaux. From that moment on, my life would change completely. I had to leave primary school, when I was almost ready for secondary school, and my chances of starting a career were cut short. The same thing happened to the rest of my brothers and sisters (there were no less than six of us), since my father, president of the Republican Employers’ Association of the city, a worker who, having become independent, had set up a small electrical shop and workshop, which placed him in a comfortable economic position. With the arrival of Franco’s troops, given his political position, he was imprisoned, his shop and workshop were closed down and his bank account emptied “for dedicating himself, in the company of clearly rebellious individuals, to listening to the red radio stations” in the shop he ran. It was probably true, although he told me later that it was not true.

We landed happily at the docks of Bordeaux and from there we were taken by train, via Toulouse, to the Franco-Catalan border, from where, on other trains that we had to wait for for a long time, we were taken to San Vicente de Torelló, where they accommodated us as best they could, spread out in various places in the town. There we formed a small refugee colony and within it, a school for children between 5 and 15 years old. After the first months of stay, in which I had to work helping in the kitchen (carrying water, splitting firewood, running various errands…), we entered a children’s colony, where I was undoubtedly happy, also thanks to the teachers we had: Don Saturnino de Diego Escudero, his wife and his two children, still very young. Don Saturnino had been spared from going to the front due to a serious limp that made him unfit for military service. I learned many things from him, but above all, his wisdom and his unwavering honesty taught me that a human being is not truly human until he has acquired irreproachable ethics. I have never forgotten him or his teachings.

When the rebel troops were approaching the border between Catalonia and France (we were not far away, as the La Coromina colony was between Montequiu and the castle of the same name), Don Saturnino decided that we should move towards France until the hostilities ceased, and when peace had come, we would have time to return. He was frightened by the barbarities that were being reported of the Italian troops passing through towns and cities. But there was also a personal reason for this decision, as we later learned: he was a right-wing man and wanted to join the Francoist troops, even at the last moment. This was, as he told me later, an unfortunate adventure that almost cost him his life, as they wanted to shoot him for having “deserted the fight.” He was saved by his limp, which justified “his lack of dedication to the cause.”

Once in France, I was cut off from my family (the two trucks carrying all the children and the teachers who accompanied us had separated), and in Dijon we were sent to a school for refugee children without families. But soon after, it was already the beginning of 1939, I began to see that a serious situation was approaching. The planes, the French troops were moving here and there, people were talking openly about the seriousness of the situation and I, who had just turned fourteen and had learned to manage on my own (you learn a lot and quickly in these situations), decided that the time had come to return home and asked to be repatriated.

I think it was April or May when I came home. The situation I found was truly catastrophic. My father had hardly any work, my older brothers were in the army and it took them two or three years to be demobilised, and my two aunts and their children were in his care and they had to be fed. At that point, my working life began, as I could not even think of beginning any kind of studies and I became an electrician, a job I did until 1959. Everything changed for me. My brother Ramón, who had remained at home, was called up to the army and I had to replace him by helping my father. Through my brother Ramón, before he left for Morocco, where he had been posted, I made contact with a group of young people, two to three years older than me, and although I didn’t know what they did, I helped them by carrying clothes, food or money to the families of the political prisoners who filled the prisons in those years, without knowing, of course, that I was going to form part of that huge group of victims and that the situation would last for forty years, more or less.

One night, when I was listening to the news on the back of the bed (we didn’t have a radio at home, it had been confiscated since the Reds – and we were considered as such – could not have such a dangerous means of communication, I heard the news that the Second World War had been declared: it was September 1, 1939. That same night I was arrested by the Political Social Brigade led by Colonel Aymard together with his second in command, the Northern Capital, with his assistant, better known as Carlitos, as he called himself. They were going to look for my brother and since they didn’t find him, they arrested me.

At the police station on Calle del Sol, where they had set up their “work” office, I met José Hierro, several other boys whom I didn’t know, and a group of seven blind men. After several days of torture (beatings, electric shocks, etc. – one of the older ones tried to commit suicide after seeing his wife being tortured by being made to watch the spectacle), when they finished with us we were taken to the Provincial Prison of Santander. In the spring of the following year, we were transferred to Madrid, to the provisional prison of the Convent of the Comendadoras. Almost a year later we were tried by a pompous military court, in a very summary trial (all political trials were by this exceptional procedure) and all the detainees were sentenced to heavy prison terms, some to death (I don’t know how many of them were carried out), except me, who was placed at the disposal of the Juvenile Court, with the obligation to present myself every week at the military court on Calle de Barquillo, being deported to this city. When I managed to return to Santander, free of charges, although no one told me that it was the case, a new stage of my life began. During my stay in the prison in my city, I came into contact with a member of the Communist Party and agreed to work with them. But it was the Francoists themselves who, with their behaviour, had convinced me that it was necessary to fight against the regime and so I did until the dictator died in 1975 and democracy was re-established. And I returned to my own thing: music.

It is true that since I returned from France and saw that my sister’s piano (which she never let me play) was free (she had moved to Madrid), I undertook the task of doing it myself, a completely illusory thought. But that piano was a catastrophic instrument and I didn’t put much effort into it until a client of my father’s (with whom I worked as an electrician’s assistant), who owned a restaurant – it had previously been a cabaret, but had been banned as a place of perdition and sex – where there was an extraordinary Erard grand piano, suggested the idea that he might let me use it. The piano was forgotten in a small room upstairs, which had been the ballroom, among several dozen kilos of potatoes that the owner kept like gold in order to support the restaurant’s food service. Right there, removing the potatoes from the floor because they prevented me from using the pedals, I began to learn music using the solfeggio books that my sister had abandoned.

Above my house lived the owner of a fishmonger’s shop, whose business was in turn on the ground floor of the building. One day, my mother came up excitedly with a large bundle of papers under her arm and said to me: “Look what I found at the fishmonger’s, where they had it to wrap the fish,” and she showed me a pile of musical scores. They were the first fifteen piano sonatas by Beethoven, all of Mozart’s, some by Mendelssohn and several other pieces that didn’t attract my attention. The Moonlight and some other pieces were missing from the Beethoven collection, and what didn’t interest me (what could I know if I barely knew classical music?) I returned them to be used to wrap fish. I don’t know who I condemned to such a low task.

Meanwhile, in Santander, the Philharmonic Society concerts had resumed, which during the season were held at the Cervantes Cinema. From the little money my father could give me, I saved up with a titanic effort, so that I could go to some of them. It was these concerts that finally resolved – together with the common sense that told me that I could never become a performer – my doubts about the future that music offered me: I would dedicate myself to writing wonderful works that would elevate me to the category of my two gods, Mozart and Beethoven. Nothing less. I had not yet reached twenty years of age and it was logical that I would be able to take on the world. But the study to achieve this feat would take me the next twenty or thirty years… and I have not yet finished, far from reaching the minimum height that I know I should have, not to reach such height, but to get a little closer.

From then on, all my money went into buying new scores, music paper that I would scribble feverishly and then tear up in desperation, although I did not give up on my idea of becoming a true composer.

I met Carmen Vélez at the home of José Hierro, who had recently been released from prison. We got married in December 1947 and I did not have a few years of peace until 1952, when she left the hospital after having undergone a thoracoplasty operation to eliminate tuberculosis that had almost cost her her life. Around 1943 (I am not too sure of the date), I was saved from a new “fall” – in political jargon a wave of arrests – thanks to the fact that my link with the organisation had died in a concentration camp in the Canary Islands, on the island of Hierro and I was isolated from the party until 1952 when two other active members, Daniel Gil and his wife, Monica Acheroff, put us back in touch with the leadership through our friend Jean Rony. I began to work politically and managed to reorganise those who remained free of suspicion until the end of the summer of 1958, when Carmen and I had to go into exile in France before the police could catch up with us.

In a situation like this, it was difficult for me to write music, although I made some strange attempts, not very successful, that is the mildest qualification I can give. Already settled in France – although I entered Spain clandestinely approximately every two months, working in the area of Asturias, where the organisation had been totally dismantled by the police – I tried to compose some works. From then are the Second Piano Sonata and some small works that I lost in my next arrest. This took place in Avilés in 1960, together with seven other members of the Asturias leadership, of which I was politically responsible and when we were preparing the great strikes that would take place in 1961, when we were already in the Oviedo prison.

Sentenced to a total of fifteen years in prison. There should have been twenty, but the pressure from the street was too high and they had to lower the fiscal demands when the normal thing was to raise them if the prisoners proclaimed our ideas during the few words they allowed us to say to defend ourselves.

But it seems that fate was in favour of my studying music and the five years of imprisonment that I served, first in the Oviedo Prison and later in the Burgos Penitentiary, served me to finish the studies that I had poorly carried out on harmony, counterpoint and orchestration.

I will never be able to thank Jean Wiener enough, the French composer with whom I had had some conversations during my stay in Paris, for the interest he showed in my work and the sound advice and help he gave me. I sent him a work for a string quintet and clarinet, written in Oviedo, and he gave me back this advice: study, you lack knowledge of counterpoint and orchestration. And together with this advice he sent me the four volumes of Charles Koeklin’s Treatise on Orchestration and a good treatise on counterpoint. And that was my work during the years of my stay in Burgos, of which the First and Second String Quartets, the Third Piano Sonata, a series of songs, small piano works and the sketches of an orchestral work that was not completed (converted into chamber music for a wind instrument and three or four strings) until 2009, with the title Twelve Goya Engravings remained.

When I left prison, at the end of December 1965, I intended to rest, but I could not do so. I had to work politically to reorganize the party, which had once again been wiped out by the continuous arrests that the police periodically carried out. But as I had to eat and therefore make a living doing translations from French, or preliminary studies for the presentation of works by classics, I had to go to Madrid, where I got a job in a publishing house run by Francisco Pérez González. From then on, when I had serious doubts about the role of the Communist Party and the undue participation of the USSR in the political affairs of the rest of Europe, I decided that my participation in the struggle would have to be less direct. I had barely been in my job for two years when one night the police knocked on my door again, as always, at three in the morning. The Santander organization had fallen into their hands and a good part of the detainees had “sung” that I was the one who had inaugurated their new stage of work. Transferred to Santander in 1968, I went back to prison. But this time, in addition to the fact that the fearsome military courts had already been suspended, replaced by the Public Order Court, my boss and friend, Francisco Pérez González, helped by Jesús de Polanco, were able to get me out free of punishment, when the other members of the Party were sentenced to not too long sentences.

From then on, and already in vociferous disagreement with the politics of the PC, my political activity became almost non-existent. Later, in 1976, after the fall of the regime, I completely abandoned militancy. I thought that I had already done my part and that, now, I was going to dedicate myself to what had been the great dream of my life: to become a real composer, independently of the greater or lesser value of my works.

Since my retirement in 1985, I only had time to write music and most of my work is chronologically framed between the years 1980 and this year in which I write this brief biography of my life, year 2009 of the 21st century.

What remains of my life, which cannot be much, will be dedicated to this task, to the memory of my first wife, Carmen and above all to Dolça, thanking her for these fourteen wonderful years that we have spent together.

And to my friends and comrades, almost all of them gone, but always present in my memory, as present as the music I carry inside me, as Carpentier would say.

Eduardo Rincón

July 2009, in Torroella de Montgrí.

Cit. Composer’s website

THRESHOLD

At the threshold of freedom and pursued by the Nazis, Walter Benjamin committed suicide in Portbou on 26 September, 1940. This humble homage was put together from 74 photographs taken over three days in Dani Karavan’s mystical and unforgettable space.

THE PHOTO ALBUMS

Thirty years after my grandfather passed away I opened the boxes of family documents and photo albums that he left me. This film tells the story of the life and times of an expatriate Swede in Spain made entirely from images found in his personal photo albums.